Kathleen Edwards' Nostalgia Machine

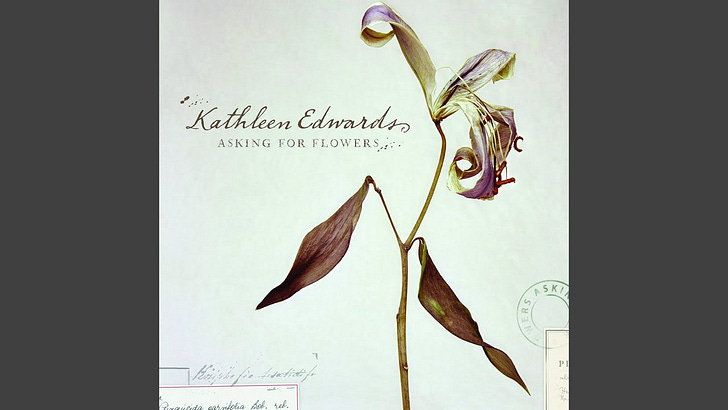

While on stage last month, Kathleen Edwards jokingly referred to her music career as a “trainwreck”, a word we usually reserve for things we have a great deal of compassion for. Her music is relatively new to me, but its stronghold developed almost immediately. Edwards’ voice is disarmingly clear, and her lyrics are blunt, almost distractingly so. Yet their obvious sincerity and her emotive shaping have kept me playing all her albums -but especially Back to Me, Asking for Flowers, and Total Freedom- nearly nonstop. Buying a ticket was a no brainer.

The thing that struck me most about Edwards when she walked on stage was her seeming indifference towards the audience. It wasn’t disinterested or dismissive. It felt confident, and had more an air of I would be doing this even if you weren’t here, and I loved it. This is one of my favorite qualities in a musician. She’ll play music, and if you’re around, you get to hear it; a fair barter.

When at a concert, there is perhaps nothing better than hearing that song, that one song, you’re dying to hear. Sometimes I fantasize about being a concert goers who holds up a sign with the song’s title on it, or worse, yells it out from the audience. But I’m sane, so I never do. And anyway, it’s so satisfying when it happens organically, like I am on some secret wavelength that only people with impeccable taste can pick up. In reality, we often have the same favorite tracks because a good song speaks to private experiences that nearly everyone has had (insert that adage about the personal being universal). So when the three opening notes of Goodnight California chimed and Edwards pulled a bow across her violin, the entire audience clapped along with me, relieved.

More than any other song, I think Goodnight California showcases Edwards’ vocal depth and control. With impressively sparse lyrics, it’s a painfully honest song detailing an imagined reuniting between two people who I read as past lovers:

You know what I wish? It was just you and me Sitting in this corner bar You could tell me how your are But I'm not gonna lie or anything You don't even have to speak If you keep looking at me And I could go all night But they're turning up the light It would be so easy Do or say anything And I'm not gonna lie I'm not looking for love I won't let you in my heart But you were always on my mind

Sitting in the back of the tiny Waldo Theatre in Waldoboro, Maine, I am mere miles from a corner bar I wish desperately to go to after the show. It’s nearly two years to the date that I was there with someone who is often (read: always) on my mind these days. And it’s that relationship I think of whenever I hear this song. Now, it’s more visceral than ever. I can smell the salty dampness of a seaside dive, taste the dry aftertaste of a cheap beer, and feel a rough hand on my knee as I listen to music, alone, that is only able to mean something to me in the total absence of what I know are pure imaginations.

I’m embarrassed by this tendency to bring the past into my present, carrying it around with me like a postcard I wrote to myself. Wish you were here! Then I remember that the woman standing on stage who I am so impressed with and entranced by has been singing songs about her past all night, confidently carrying it into the present. Glenfern, another personal favorite that I was excited to hear live, detours from Edwards’ usual biting lyricism. Woven inbetween verses that depict the early days of a relationship, the chorus repeats “I will always be thankful for it”, eventually leading to the bridge that declares “I am sorry for everything.” It’s perhaps the gentlest gut punch I’ve ever felt.

Towards the end of the night, Edwards played a forthcoming track deriding the pressure for musicians to cater to the algorithms of streaming services and social media. A bit of a Luddite myself, I’m not typically one to defend the non-analog. But as I write this from a bare bones cabin motel in mid-coast Maine, I can’t help but laugh to myself. It was an algorithm that correctly assessed (I don’t want to know how) that a 30-year-old woman weighed down by heartache and reeling from her Saturn return would want to hear Options Open, Edwards’ sympathetic confrontation of her own indecision, with lines like “it’s not my fault that I wasn’t sure” and “you don’t have to say it, ‘cause nobody’s harder on me than me”. And because the algorithm got that right, I dug into the rest of the catalogue, which flagged me as a fan, resulting in an in-app notification about upcoming shows I might like to see, and my subsequent ticket purchase. I think, as a final note, that this is not so bad for making a career out of playing music with your friends, as Edwards describes it. Certainly nothing I would call a trainwreck.